Australian Publisher Yuri Tkacz

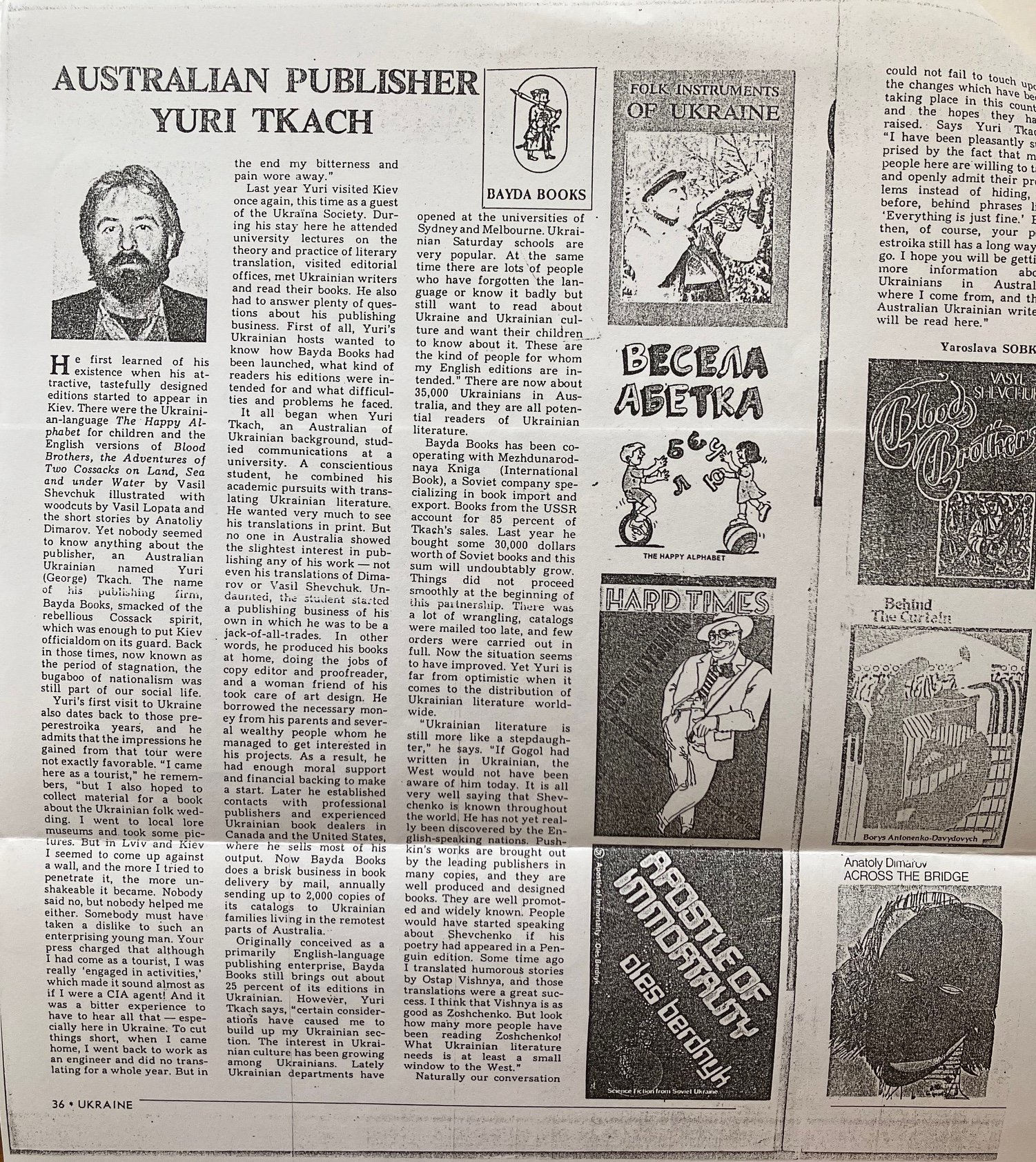

We first learned of his existence when his attractive, tastefully designed editions started to appear in Kyiv. These included the Ukrainian-language The Happy Alphabet for children and the English versions of Blood Brothers, The Adventures of Two Cossacks on Land, Sea and Underwater by Vasil Shevchuk (illustrated with woodcuts by Vasil Lopata), and the short stories by Anatoliy Dimarov. Yet, nobody seemed to know anything about the publisher—an Australian Ukrainian named Yuri (George) Tkacz. The name of his publishing firm, Bayda Books, smacked of the rebellious Cossack spirit, which was enough to put Kyiv officialdom on its guard. Back in those times, now known as "the period of stagnation," the bugaboo of nationalism was still part of social life.

Yuri's first visit to Ukraine also dates back to those pre-Perestroika years, and he admits that the impressions he gained from that tour were not exactly favorable. “I came here as a tourist,” he remembers, “but I also hoped to collect material for a book about the Ukrainian folk wedding. I went to local museums and took some pictures. But in Lviv and Kyiv, I seemed to come up against a wall, and the more I tried to penetrate it, the more unshakable it became. Nobody said no, but nobody helped me either. Somebody must have taken a dislike to such an enterprising young man. Your press charged that although I had come as a tourist, I was really ‘engaged in activities,’ which made it sound almost as if I were a CIA agent! And it was a bitter experience to hear all that—especially here in Ukraine. To cut things short, when I came home, I went back to work as an engineer and did no translating for a whole year. But in the end, my bitterness and pain wore away.”

Last year, Yuri visited Kyiv once again, this time as a guest of the Ukraina Society. During his stay here, he attended university lectures on the theory and practice of literary translation, visited editorial offices, met Ukrainian writers, and read their books. He also had to answer plenty of questions about his publishing business. First of all, Yuri's Ukrainian hosts wanted to know how Bayda Books had been launched, what kind of readers his editions were intended for, and what difficulties and problems he faced.

It all began when Yuri Tkacz, an Australian of Ukrainian background, studied communications at university. A conscientious student, he combined his academic pursuits with translating Ukrainian literature. He wanted very much to see his translations in print, but no one in Australia showed the slightest interest in publishing any of his work—not even his translations of Dimarov or Vasil Shevchuk. Undaunted, the student started a publishing business of his own, in which he became a jack-of-all-trades. In other words, he produced his books at home, doing the jobs of copy editor and proofreader, while a woman friend took care of the art design. He borrowed the necessary money from his parents and several wealthy people whom he managed to interest in his projects. As a result, he had enough moral support and financial backing to make a start. Later, he established contacts with professional publishers and experienced Ukrainian book dealers in Canada and the United States, where most of his output is sold.

Now, Bayda Books does a brisk business in book delivery by mail, annually sending up to 2,000 copies of its catalogs to Ukrainian families living in the remotest parts of Australia.

Originally conceived as a primarily English-language publishing enterprise, Bayda Books now brings out about 25 percent of its editions in Ukrainian. However, Yuri notes, “Certain considerations have caused me to build up my Ukrainian section. The interest in Ukrainian culture has been growing among Ukrainians. Lately, Ukrainian departments have opened at the universities of Sydney and Melbourne. Ukrainian Saturday schools are very popular. At the same time, there are lots of people who have forgotten the language or know it poorly but still want to read about Ukraine and Ukrainian culture—and want their children to know about it. These are the kind of people for whom my English editions are intended.” There are now about 35,000 Ukrainians in Australia, and they are all potential readers of Ukrainian literature.

Bayda Books has been cooperating with Mezhdunarodnaya Kniga (International Book), a Soviet company specializing in book import and export. Books from the USSR account for 85 percent of Tkacz’s sales. Last year, he bought some $30,000 worth of Soviet books, and this sum will undoubtedly grow. Things did not proceed smoothly at the beginning of this partnership. There was a lot of wrangling—catalogs were mailed too late, and few orders were carried out in full. Now the situation seems to have improved. Yet Yuri is far from optimistic when it comes to the distribution of Ukrainian literature worldwide.

“Ukrainian literature is still more like a stepdaughter," he says. “If Gogol had written in Ukrainian, the West would not have been unaware of him today. It is all very well to say that Shevchenko is known throughout the world. He has not yet really been discovered by English-speaking nations. Pushkin’s works are brought out by leading publishers in many copies, and they are well-produced and beautifully designed books. They are well-promoted and widely known. People would have started speaking about Shevchenko if his poetry had appeared in a Penguin edition. Some time ago, I translated humorous stories by Ostap Vishnya, and those translations were a great success. I think that Vishnya is as good as Zoshchenko. But look how many more people have read Zoshchenko! What Ukrainian literature needs is at least a small window to the West.”

Naturally, our conversation could not fail to touch on the changes taking place in this country and the hopes they have raised. Says Yuri Tkacz, “I have been pleasantly surprised by the fact that many people here are willing to try and openly admit their problems instead of hiding, as before, behind phrases like ‘Everything is just fine.’ Then, of course, your Perestroika still has a long way to go. I hope you will be getting more information about Ukrainians in Australia, where I come from, and that Australian Ukrainian writers will be read here.”

Yaroslava Sobko